How Cocaine Abuse Triggers Hidden Mental Health Disorders

Table of Contents

- Cocaine’s Hidden Mental Health Fallout—What People Often Miss

- Cocaine and Depression—A Cycle of Dopamine Crash and Despair

- Cocaine-Induced Anxiety and Panic Disorders in Young Professionals

- Hidden Psychosis—When Cocaine Use Leads to Paranoia & Hallucinations

- The Link Between Cocaine and Bipolar Disorder—Masking the Highs and Lows

- Cocaine Use Among U.S. Veterans & PTSD Triggers

- Long-Term Cognitive Damage and Suicidal Thoughts

- Stigma in Seeking Help—Why Most Cocaine Users Don’t Get Mental Health Support

- Therapy That Works—How Online Therapy Is Addressing Dual Diagnosis

- Cocaine Withdrawal vs. Underlying Mental Illness—What to Treat First?

- From Relapse to Recovery—Real U.S. Stories of Healing Dual Diagnoses

- Prevention, Policy & Awareness—The U.S. Response to Cocaine’s Mental Toll

- FAQs

- Conclusion

- About the Author

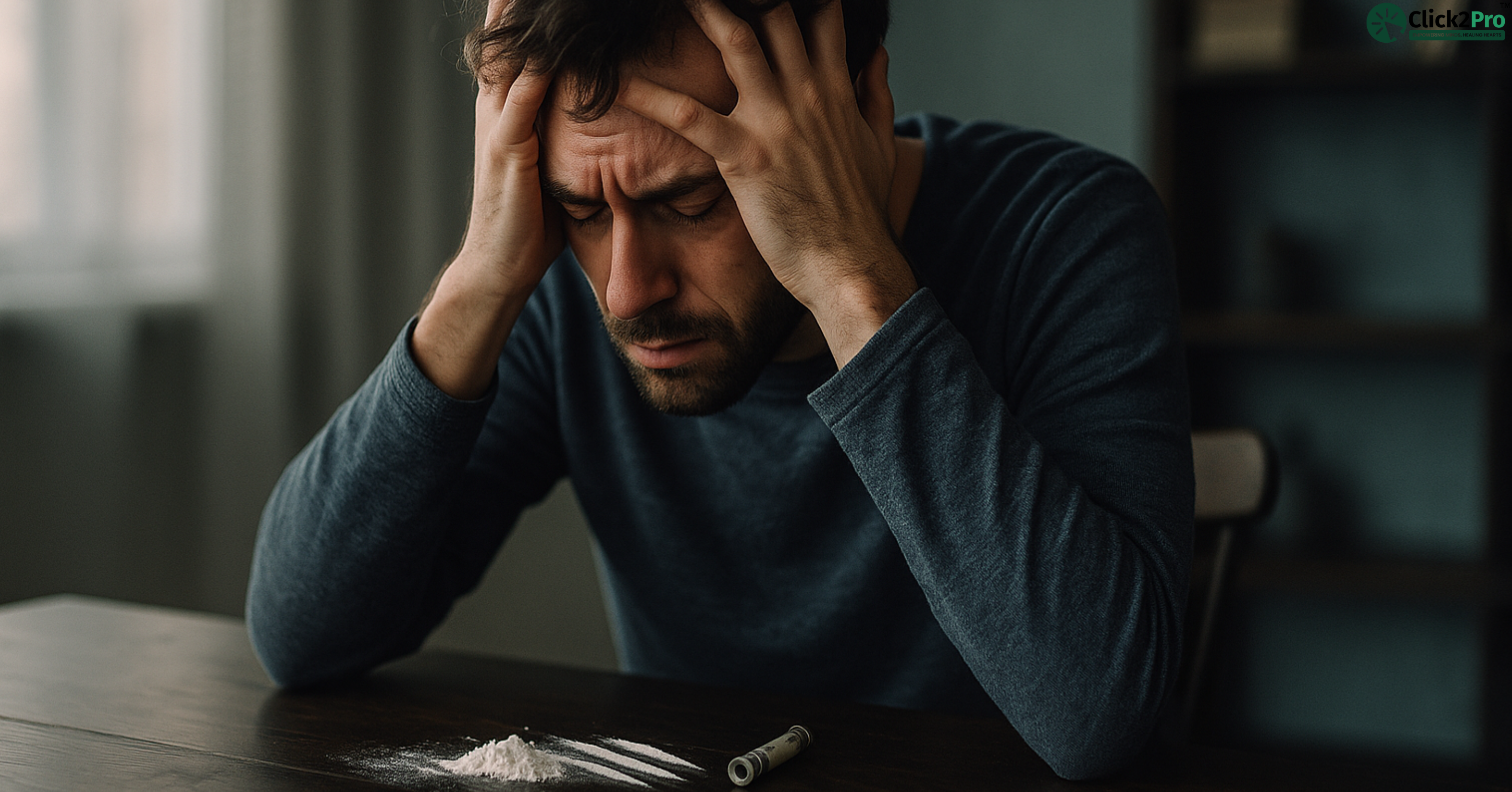

Cocaine’s Hidden Mental Health Fallout—What People Often Miss

If you only think of cocaine as a party drug, you’re missing the deeper story—one that plays out long after the high fades. Across the United States, a growing number of people are facing serious, often undiagnosed mental health disorders linked to cocaine use. But unlike what’s portrayed in movies or news reports, the damage isn’t always loud or obvious. It often shows up in quiet, dangerous ways: as panic attacks, paranoia, deep sadness, or even suicidal thoughts.

Many Americans who use cocaine never realize their brain is changing. A few nights of partying can evolve into something more—an emotional rollercoaster they can't get off. The brain’s reward system begins to misfire. Users report they can’t feel joy like they used to, even when sober. For some, the shift is subtle. For others, it’s terrifying.

In states like Florida, California, and New York, where cocaine use is prevalent among high-stress professionals—stockbrokers, creatives, even lawyers—mental health clinics are reporting spikes in co-occurring disorders. These aren’t just cases of addiction. They're people battling anxiety, depression, psychosis, and trauma that only fully emerge once cocaine use is underway. Cocaine doesn’t create mental illness from thin air, but it can certainly uncover what’s been hidden—and fast.

In many cases, individuals use cocaine to escape. A stressful job. A bad breakup. Trauma. But in trying to run away from emotional pain, they unknowingly dig deeper into it. Cocaine overstimulates the brain’s natural dopamine production. At first, this gives users a powerful rush—confidence, energy, and even euphoria. But that same rush becomes the trap. Over time, the brain produces less dopamine naturally. The result? A crash. Not just physically, but mentally. And it’s not temporary.

Here’s what many don’t know: cocaine’s mental health impact often outlives the addiction itself. Some users, even after quitting, find themselves battling mood swings, irritability, and flashbacks. Others discover they’ve developed symptoms of anxiety, paranoia, or obsessive-compulsive behavior they never had before. The drug may be gone, but the imprint remains.

This is where U.S. mental health professionals are raising concern. At treatment centers across the country—from Colorado to Ohio—counselors are urging a more thorough screening of cocaine users for mental illness. Why? Because most users aren’t just dealing with addiction. They’re walking around with undiagnosed conditions made worse by the drug—and in many cases, cocaine was the match that lit the fire.

People who casually use cocaine at parties or to stay productive at work often feel immune to its deeper consequences. But mental health doesn’t discriminate. Cocaine doesn’t either. It affects the brain, and the brain affects everything—how you think, how you feel, how you see the world. This isn’t just a drug story. It’s a mental health story hiding in plain sight.

Cocaine and Depression—A Cycle of Dopamine Crash and Despair

One of the most common and painful outcomes of cocaine abuse is clinical depression. And yet, it's also the most overlooked. While the drug may offer a quick high, it ultimately steals more than it gives—especially from the brain’s reward system.

Let’s break this down.

Cocaine spikes dopamine levels rapidly. Dopamine is the “feel good” chemical responsible for pleasure, motivation, and energy. At first, cocaine feels like magic. Users describe it as confidence in powdered form. But here’s the catch—those dopamine surges come at a cost. After repeated use, the brain adapts. It stops producing and absorbing dopamine in normal ways. In simple terms, your natural ability to feel good gets broken.

This leads to what’s known as a dopamine crash, and for many, it feels like hitting an emotional brick wall. You feel numb. Exhausted. Empty. Things that used to bring joy—like relationships, hobbies, or work—don’t register anymore. Over time, this dullness becomes something deeper. Sadness. Hopelessness. A loss of purpose. That’s when cocaine use crosses over into depression.

In cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, addiction recovery centers report that nearly 6 out of 10 clients struggling with cocaine also show symptoms of clinical depression. In Los Angeles, several mental health outpatient programs have launched dual-diagnosis tracks just to address this overlap.

But depression triggered by cocaine isn’t always easy to diagnose. That’s because withdrawal symptoms—like fatigue, irritability, and lack of interest—can mimic depression. Many users go undiagnosed because they assume they’re just “coming down.” The danger here is that the real depression gets masked by the temporary symptoms of withdrawal. And when it’s not treated, it grows.

This often leads to a dangerous cycle. A person feels low after using cocaine, so they take more to feel better. It works—for a while. Then comes the crash. The low feels even lower than before. So they use it again. This repetitive loop wears down mental stability. Eventually, the high no longer works, and the lows become unbearable. That’s when suicidal thoughts can creep in. For some, those thoughts become actions.

Mental health professionals across the U.S. are seeing this pattern in teenagers, young adults, and even executives in their 40s. The external lifestyle may look intact. But inside, they’re drowning.

In states like Michigan and Pennsylvania, community health programs have started awareness campaigns targeting this very issue: “If your lows feel worse than they should, it might not just be the crash—it might be depression.” This isn’t just about helping people quit cocaine. It’s about helping them understand that their emotional health is under attack—and that it’s okay to ask for help.

There’s hope in this conversation too. When depression is treated alongside addiction, recovery outcomes improve dramatically. Talk therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other approaches can help reset the brain’s reward system over time. But the first step is awareness. Recognizing that what feels like a crash may be something deeper—and that you’re not alone in it.

Cocaine-Induced Anxiety and Panic Disorders in Young Professionals

For many young professionals across the U.S.—especially in high-pressure careers like tech, finance, and media—cocaine isn’t viewed as a hard drug. It’s seen as a productivity enhancer or a party fuel. In cities like New York, Miami, and San Francisco, it’s often normalized in social circles where burnout is high and downtime is rare.

But what begins as an energy booster or social lubricant can quickly trigger something more dangerous: chronic anxiety and full-blown panic disorders.

Cocaine activates the body’s fight-or-flight system. It speeds up the heart, increases blood pressure, and raises cortisol—the stress hormone. For first-time users, this rush may feel thrilling. But for repeat users, especially those under ongoing work or personal stress, this overstimulation can spiral. The brain begins to interpret everyday situations—like a work meeting or traffic jam—as threats.

That’s when anxiety sets in.

Users report restlessness, overthinking, chest tightness, and sudden fear. These symptoms often appear even when they haven’t used cocaine for days. The drug alters how the brain manages fear and tension. Once the brain is trained to operate in a heightened state, it doesn’t switch off easily.

In places like Boston and Chicago, behavioral health clinics have reported a surge in young adults seeking treatment for anxiety and panic—many of whom also disclose recent cocaine use. Yet most don’t connect the two. They think the panic attacks are random. But underneath it all, the nervous system is reacting to something deeper: overstimulation, emotional suppression, and chemical disruption.

Some professionals use cocaine to mask imposter syndrome or performance anxiety. They think it helps them stay sharp. But the truth is, it often worsens the very insecurities they’re trying to numb. Over time, the brain becomes hypersensitive. Normal interactions start to feel overwhelming. Relationships suffer. Sleep becomes impossible. And the pressure keeps building.

What’s more troubling is that anxiety related to cocaine use doesn’t always stop when the drug does. For many, the withdrawal period brings its own storm—intense agitation, restlessness, and physical tension. Some people experience panic attacks weeks after quitting. That’s because the body is trying to reset, but it’s out of rhythm.

Mental health specialists in states like Washington and Colorado have started referring to this phenomenon as "stimulant-triggered anxiety syndrome." It’s a term used to explain anxiety disorders that emerge or worsen after extended stimulant use—even when the person doesn't consider themselves an addict.

Fortunately, anxiety rooted in cocaine abuse can be treated. Therapies like CBT, grounding exercises, and guided exposure work well. But it starts with awareness. If you’re feeling more anxious than usual, and you’ve used cocaine—even casually—it’s worth asking whether the two might be connected. Because anxiety isn't always in your head. Sometimes, it's in your history.

Hidden Psychosis—When Cocaine Use Leads to Paranoia & Hallucinations

Among the most serious yet misunderstood consequences of cocaine use is psychosis. Unlike anxiety or depression, cocaine-induced psychosis doesn’t always build gradually. In some cases, it can hit like a switch—transforming a person’s thoughts, perceptions, and behavior almost overnight.

Psychosis refers to a break from reality. It includes symptoms like paranoia, hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren’t there), and delusional thinking. When cocaine is involved, this break often comes during heavy or binge use. However, it can also show up in people who think they’re “just casual users.”

Imagine this: You’re at a friend’s place, using cocaine to stay alert. Suddenly, you begin to feel watched. You’re sure someone’s outside the window. You hear footsteps that others don’t. You accuse people of plotting against you. You may even barricade the door. This isn’t rare. It’s cocaine psychosis—and it’s terrifying.

In cities like Detroit, Atlanta, and Phoenix, emergency rooms are seeing increasing cases of cocaine-related psychotic episodes. And according to data from U.S. psychiatric units, nearly 35% of patients admitted for stimulant-induced psychosis had used cocaine in the week prior to their admission.

What’s even more concerning is how cocaine psychosis can resemble serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia. The two are often confused, especially during the first episode. The hallucinations feel real. The paranoia is intense. And the person may not believe they’re experiencing anything unusual. Friends and family often notice the shift first—sudden aggression, irrational behavior, or wild accusations.

In some individuals, especially those with genetic vulnerabilities or early trauma, a single cocaine-induced psychotic break can open the door to ongoing mental illness. That’s why U.S. psychologists stress that this isn’t just a drug issue—it’s a mental health emergency.

Even after stopping cocaine, some users report lingering paranoia or suspicious thinking for weeks or months. This is called persistent psychosis, and it can be deeply isolating. People stop trusting others. They withdraw socially. They question their memories. It’s like walking through life with distorted glasses—and not knowing how to take them off.

Treatment typically involves antipsychotic medications, behavioral therapy, and close psychiatric monitoring. But most people suffering from cocaine psychosis don’t seek help until it becomes a crisis. That delay can be dangerous—not just to the person affected, but to others around them.

Law enforcement agencies in states like Nevada and Missouri have noted an increase in 911 calls involving hallucinations or aggression linked to cocaine use. Many of these incidents could be avoided with earlier mental health support and public education.

The lesson is simple but urgent: If someone begins showing signs of paranoia or hallucination after using cocaine, even just once, it must be taken seriously. Psychosis is not a moral failure. It’s a medical condition. And when it’s triggered by a drug, it often needs professional treatment—not just detox.

The Link Between Cocaine and Bipolar Disorder—Masking the Highs and Lows

In the mental health world, few conditions are as misunderstood—and misdiagnosed—as bipolar disorder. Add cocaine into the mix, and the waters become even murkier. Many people who use cocaine regularly display erratic mood shifts. But what happens when those shifts aren’t just drug-related? What if they reveal a deeper disorder beneath the surface?

Cocaine and bipolar disorder often overlap. And that’s not a coincidence.

Bipolar disorder is marked by extreme highs (mania) and lows (depression). The highs can look like confidence, energy, impulsivity, and grand ideas. In some cases, people feel invincible. These manic episodes can look almost identical to what someone experiences when high on cocaine. Now imagine someone already prone to mania using a stimulant like cocaine. The results can be explosive—and dangerous.

Here’s where it gets tricky: many individuals with undiagnosed bipolar disorder use cocaine to self-regulate. When they’re in a depressive slump, cocaine gives them a lift. When they’re manic and can’t slow down, the crash that comes after using them can mimic sedation. It’s a see-saw that tricks the brain into thinking it’s gaining control—when in reality, it’s losing it.

Psychiatrists in Texas and New Jersey have increasingly reported cases of young adults being misdiagnosed with substance-induced mood disorder, when in fact they have underlying bipolar disorder made worse by stimulant use. That delay in diagnosis can be life-altering. Without proper mood stabilization, the person may keep chasing relief through cocaine—never realizing their real battle is neurological.

One patient in Austin, a 32-year-old entrepreneur, described how he used cocaine on weekends to “balance his mood swings” without realizing he was in the middle of a manic episode. It wasn’t until he was hospitalized after a paranoid breakdown that bipolar I disorder was finally diagnosed.

The use of cocaine also makes medication management difficult. Drugs like lithium or lamotrigine used to treat bipolar disorder interact poorly with the ups and downs created by stimulants. That’s why dual-diagnosis treatment is essential. In states like Oregon and Pennsylvania, mental health centers now run specialized tracks for bipolar clients with a history of stimulant use.

The emotional toll is massive. People who live with bipolar disorder already struggle to trust their own feelings. When cocaine is added, that self-doubt magnifies. Was it just the drug talking—or is this how I really feel? This internal confusion often leads to isolation, shame, and a delay in seeking help.

If you or someone you know is swinging between intense highs and crushing lows, and cocaine is part of the story, it’s time to ask deeper questions. Because masking bipolar symptoms with cocaine may offer temporary calm—but the storm always returns stronger.

Cocaine Use Among U.S. Veterans & PTSD Triggers

In the United States, one of the most heartbreaking intersections of trauma and substance use is found among military veterans. The connection between PTSD and cocaine use is rarely discussed outside of clinical settings, but it’s very real—and growing.

Veterans returning from combat often carry invisible wounds. Flashbacks, hypervigilance, insomnia, and emotional numbness are just some of the symptoms tied to post-traumatic stress disorder. These symptoms can feel unbearable. And for many, cocaine seems like a way out—an escape, a numbing agent, or a source of false energy in a world that no longer feels safe.

In VA centers across North Carolina, Georgia, and Texas, addiction specialists are reporting that a significant portion of veterans with PTSD also report past or ongoing cocaine use. In fact, some studies have found that veterans with PTSD are nearly twice as likely to develop a cocaine use disorder compared to their non-PTSD peers.

Why cocaine? Because it’s fast-acting and powerful. It can make a veteran feel in control again—temporarily. It replaces numbness with intensity. It distracts from pain. It quiets flashbacks, if only for a night. But the trade-off is brutal. Once the high fades, symptoms come back stronger. The brain’s already-fractured stress response system becomes even more fragile.

One Iraq War veteran in Denver described how cocaine became a nightly ritual. “It made me feel alive again,” he said. “But every morning I woke up deeper in the pit.”

The cycle is fueled by silence. Many veterans, especially men, are taught to avoid showing emotional pain. They may feel weak admitting to mental health struggles. Cocaine becomes a coping mechanism they can hide behind. But eventually, it stops working. The hypervigilance turns into paranoia. The numbness becomes depression. The energy becomes aggression. And relationships begin to fall apart.

This is not a failure of willpower—it’s the collision of trauma and chemistry.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has started rolling out dual-diagnosis treatment programs specifically for stimulant users with PTSD. In states like Arizona and Michigan, mobile outreach teams are also connecting with homeless veterans, a population especially vulnerable to cocaine-related mental illness.

Peer support is now a critical part of treatment. Veterans tend to trust other veterans. In one California program, group therapy run by former service members saw a 40% higher retention rate compared to traditional group therapy models. Shared language and experience can create safe spaces that formal therapy often can’t.

It’s time we stop treating cocaine use among veterans as “just addiction.” For many, it’s a response to unprocessed trauma. Healing doesn’t come from punishing drug use—it comes from understanding why it started in the first place.

Long-Term Cognitive Damage and Suicidal Thoughts

Cocaine isn’t just a short-term stimulant—it leaves long-term scars on the brain. While most people think about the immediate dangers of cocaine (like overdose or heart attack), few understand how deeply it can reshape the mind over time. Long after the drug is gone from the bloodstream, its effects can linger in memory, impulse control, and emotional regulation.

One of the most concerning impacts is on the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for decision-making, risk assessment, and emotional processing. Studies from U.S. neurological research centers show that long-term cocaine users often display changes in this region similar to those seen in patients with brain injuries.

This kind of damage doesn’t always show up as dramatic behavior. Sometimes it looks like forgetfulness. Poor judgment. Emotional outbursts. Difficulty focusing. Losing track of time. Struggling to manage relationships. Over time, these cognitive disruptions affect how a person functions at work, at home, and in society.

In cities like Seattle and Minneapolis, mental health professionals working in outpatient recovery programs have seen a sharp rise in clients presenting with executive dysfunction—a cluster of symptoms that includes disorganization, low motivation, and impaired memory—following years of stimulant abuse.

But the real danger? Suicidal ideation.

When someone feels they can no longer trust their thoughts, or when nothing seems to “work” emotionally, the sense of hopelessness becomes heavy. Many long-term cocaine users describe feeling like they’ve “lost themselves”—their joy, identity, and ability to feel anything deeply. This emotional flatness, or anhedonia, often leads to thoughts of self-harm or giving up entirely.

According to data from U.S. suicide prevention hotlines, callers reporting cocaine use are more likely to express active suicidal thoughts than those with alcohol use disorders. In Missouri and South Carolina, local crisis response teams have been trained to ask about past stimulant use when assessing suicide risk.

The terrifying part is that many people experiencing this don’t link their mental state to past cocaine use. They assume they’ve become “weak” or “lazy” or are just naturally broken. In reality, their brain is still recovering. And recovery, while slow, is absolutely possible.

Cognitive therapy, EMDR, and behavioral activation techniques can help retrain the brain and restore emotional depth. But healing begins with recognition. If someone feels like they’ve “changed” after years of cocaine use—if life feels harder, if emotions feel dulled—it’s not just in their head. It’s in their brain. And help is possible, even after years of use.

Stigma in Seeking Help—Why Most Cocaine Users Don’t Get Mental Health Support

For all the talk about mental health awareness in America, stigma still holds many people back—especially when it comes to cocaine use. While public campaigns around alcohol and opioids have grown, stimulant abuse remains hidden in shame. And that silence keeps people sick.

In industries like construction, law enforcement, trucking, and even medicine, cocaine is sometimes used as a tool—something to get through long hours, stay alert, or numb emotional fatigue. But when the crash hits, and mental health starts to unravel, many feel they can’t speak up. The fear of being labeled weak or unstable overrides the need for help.

This fear is especially strong in small towns across the Midwest and South—places like Arkansas, Iowa, and Mississippi—where seeking therapy still carries a heavy social cost. Some believe that asking for help means losing your job. Others worry about being judged by family or church communities. And many simply don’t have access to quality mental health care nearby.

Even in cities like Dallas or Denver, professionals earning six-figure salaries often hide their mental health issues. Cocaine is considered a private vice—a secret they can manage. Until it manages them.

What makes cocaine-related stigma worse is that it's tied to a false belief: that users chose this life. But addiction rarely starts with a conscious decision. It starts with pain. With pressure. With trying to cope. And when that attempt to cope backfires, people often feel too ashamed to say, "I need help."

At Click2Pro and other mental health platforms offering online counselling, therapists report that a significant portion of clients wait 6–12 months after experiencing clear mental health symptoms before reaching out. By that time, issues like anxiety, depression, and paranoia have often worsened.

That delay isn't due to laziness—it's a stigma in action.

Another reason people hesitate is fear of being misunderstood. They don’t want to be seen as criminals or unstable. They want to be seen as human—hurting, but trying.

In response, several U.S. states are funding low-barrier mental health access programs. California, Massachusetts, and New Mexico have invested in mobile therapy vans and digital crisis lines that allow anonymous support. These efforts are slowly changing the landscape. But for real progress, cultural attitudes must shift too.

Mental health support shouldn’t be a privilege or a confession—it should be a right. If you've used cocaine and now find yourself battling emotions you can’t explain, it doesn’t make you weak. It makes you human. And humans deserve support—not silence.

Therapy That Works—How Online Therapy Is Addressing Dual Diagnosis

For decades, cocaine addiction and mental illness were treated as separate issues. A person might enter rehab for drug use, only to discover that their depression, anxiety, or trauma remained untouched. Others sought therapy for emotional struggles, unaware that their cocaine use was quietly fueling the symptoms. But now, things are changing—especially with the rise of online therapy.

Online platforms across the U.S.—including Click2Pro and other teletherapy services—are bridging the gap with what’s known as dual-diagnosis treatment. That means treating both the addiction and the mental illness at the same time, not one after the other. This approach is saving lives.

In states like Colorado, Illinois, and Arizona, online mental health services have surged, especially after the pandemic normalized remote care. What once felt impersonal is now deeply personal, allowing clients to open up from the privacy of their homes. This matters a lot for cocaine users who carry shame, secrecy, or fear around their addiction.

Why does online therapy work so well here?

Because many cocaine users are high-functioning. They’re professionals. Parents. Entrepreneurs. They can’t take time off to enter inpatient programs. But they can schedule an evening session with a trauma-informed therapist. They can text a counselor at midnight during a crash. They can attend group sessions without ever walking into a clinic.

And when mental health is addressed alongside addiction, recovery sticks better.

Therapies like CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) help users reframe negative thought patterns and interrupt the shame spiral. DBT (Dialectical Behavior Therapy) teaches emotional regulation, especially useful for those with mood swings or trauma. For deeper issues like PTSD or early-childhood trauma , EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) is proving powerful—even online.

In many states, insurance is now covering online therapy for addiction. Medicaid expansion in places like Oregon, New York, and Washington has made therapy more accessible to low-income and rural clients who would otherwise go untreated.

Some platforms also offer peer support rooms where clients can speak with others facing similar struggles. A mother in Michigan might connect with a veteran in Texas. Both carry pain. Both are learning to heal—together. That kind of human connection, even through a screen, is often the missing piece.

Online therapy isn’t a shortcut. It’s a lifeline. And for people silently struggling with cocaine and its mental health impact, it might be the first step toward real, lasting change.

Cocaine Withdrawal vs. Underlying Mental Illness—What to Treat First?

When someone stops using cocaine, the symptoms can be intense. Fatigue, mood swings, agitation, insomnia, and cravings are just the beginning. But what happens when these symptoms overlap with mental illness? And how can a person—or their therapist—tell the difference between withdrawal and something deeper?

This is one of the most common dilemmas in treatment: figuring out what to treat first. The answer? Both—carefully, and together.

Withdrawal from cocaine typically lasts between 1 to 3 weeks. During this time, a person may feel emotionally unstable, detached, or severely irritable. These symptoms can mimic depression or anxiety, but they usually fade as the body detoxifies. However, if those symptoms linger—especially after four weeks or more—it’s often a sign of an underlying mental health condition.

This is where clinical observation becomes crucial.

At dual-diagnosis centers across the U.S., including clinics in California and Florida, therapists use a staged approach:

-

First, stabilize the physical symptoms of withdrawal through rest, hydration, and non-addictive medication (like melatonin for sleep).

-

Then, begin mental health screenings to assess for mood disorders, trauma, or cognitive disruption.

If a person starts therapy too early—while their brain is still fogged by detox—the work may not stick. But waiting too long risks losing engagement or missing serious psychiatric issues.

One technique therapists use is called timeline mapping. It involves tracking when certain symptoms began and whether they existed before cocaine use. For example, if panic attacks were already present at age 18—years before cocaine use began—then anxiety is likely a primary condition, not just a withdrawal effect.

Another strategy is trial therapy. After withdrawal symptoms ease, therapists may use structured CBT to see how the brain responds. If mood improves quickly, it may have been substance-induced. If the client stays flat, it’s time to explore deeper.

This distinction is especially important when prescribing psychiatric medication. Giving antidepressants too early, or without understanding stimulant effects, can cause emotional dysregulation. That’s why experienced therapists take a slow, steady approach. They build trust. They monitor. And most of all, they listen.

People often fear being misdiagnosed. “What if I’m just broken?” they ask. But the truth is, most people aren’t broken—they’re buried under layers of trauma, chemical changes, and silence. Getting sober clears the path. Therapy uncovers the rest.

Recovery isn’t linear. It doesn’t follow a timeline. But with the right support, even the most tangled cases can become clear. And for those unsure what’s real and what’s withdrawal, therapy offers answers—and hope.

From Relapse to Recovery—Real U.S. Stories of Healing Dual Diagnoses

Recovery from cocaine addiction—especially when mental health issues are involved—isn’t a straight road. It’s a winding path filled with setbacks, breakthroughs, and small, hard-won victories. But people do recover. And their stories matter.

Take Ava, a 28-year-old graphic designer from Los Angeles. For two years, cocaine helped her survive the pressures of the creative industry. She felt “superhuman” on the drug. But after long nights came deep crashes—panic attacks, self-hate, and isolation. When she finally reached out to an online therapists near me through her employer’s wellness platform, she was diagnosed with major depressive disorder. With CBT, structured sleep therapy, and emotional support, Ava slowly came off the drug—and found joy in her work again.

Then there’s Mike, a 41-year-old veteran in Georgia. After returning from Afghanistan, he struggled with PTSD. Cocaine offered a break from the flashbacks. It also nearly cost him his marriage. After a breakdown during the holidays, Mike entered a VA-sponsored dual-diagnosis program. There, he was able to connect with other veterans. He started EMDR therapy, worked through past trauma, and found new ways to manage triggers—without drugs.

In Pennsylvania, Laura—a single mother and accountant—hid her cocaine use for years. When her anxiety became unbearable, she started virtual therapy. Her therapist noticed she wasn’t just anxious—she was showing signs of undiagnosed bipolar II disorder. With treatment, her need for cocaine diminished. “For the first time,” she shared in group therapy, “I feel like my emotions make sense.”

These stories highlight one truth: healing happens when the whole person is treated—not just the symptoms. Real people, in real states, living complex lives, are breaking the silence. And when they do, they often find support in unexpected places.

Prevention, Policy & Awareness—The U.S. Response to Cocaine’s Mental Toll

While recovery stories offer hope, the growing link between cocaine and mental illness is still a major public health challenge. Fortunately, policy changes and awareness efforts are starting to reflect this reality.

In 2024, several U.S. states increased funding for dual-diagnosis treatment centers, with Massachusetts, Michigan, and Oregon leading the way. These centers now combine psychiatric care with addiction recovery—something that was rarely done just a decade ago.

In New Mexico, state-funded mobile therapy vans now visit rural communities weekly, offering confidential counselling and referrals for stimulant users who might otherwise go untreated. These outreach programs have seen a 25% increase in engagement since launching.

Nationally, SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) has added specific language about cocaine-related mental health disorders in its training modules. This shift helps clinicians screen more accurately for co-occurring conditions during intake.

Schools, too, are stepping in. In places like Illinois and Washington, health classes are beginning to teach students not just about drugs—but about emotional regulation, trauma, and healthy coping mechanisms. Because the sooner someone understands their feelings, the less likely they are to reach for substances to numb them.

But education alone isn’t enough.

Stigma remains a major barrier, especially in underserved communities. That’s why several U.S. nonprofits have launched anonymous peer-support hotlines, where people can talk to others in recovery without judgment. Many callers say it's the first time they’ve ever shared their struggles out loud.

The message is slowly changing—from punishment to understanding, from silence to solutions. Cocaine addiction isn’t just a drug problem. It’s a mental health issue in disguise. And America is starting to listen.

FAQs

1. Can cocaine use cause permanent mental illness?

Yes. Chronic cocaine use can lead to long-term changes in brain chemistry. This may result in lasting conditions such as depression, anxiety, or stimulant-induced psychosis—even after quitting.

2. Why do I feel anxious and paranoid days after using cocaine?

Cocaine stimulates the brain’s stress circuits. Even after the drug wears off, your nervous system may remain in a heightened state, causing ongoing anxiety or paranoia.

3. How can I tell if I’m experiencing withdrawal or depression?

Cocaine withdrawal typically lasts 1–3 weeks. If sadness, fatigue, or lack of interest persists beyond that, you may be dealing with co-occurring depression. A licensed therapist can help assess this.

4. Is it common to relapse while struggling with mental illness?

Yes. Without treating the underlying mental health issue, many people relapse. That’s why dual-diagnosis therapy is key—it helps stabilize both the emotional and behavioral side of recovery.

5. What kind of therapy works best for people with both cocaine addiction and mental health issues?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), EMDR (for trauma), and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) are all effective. Online therapy platforms now make these treatments more accessible across the U.S.

6. Why don’t more people get help for cocaine-related mental health issues?

Stigma, lack of awareness, and limited access—especially in rural or underserved communities—often prevent people from seeking help. Many also don’t realize their symptoms are connected to cocaine use.

Conclusion

Cocaine doesn’t just disrupt your weekend or wreck your body—it hijacks your brain, rewires your emotions, and often hides the deeper issues that need healing most. For too long, the conversation around cocaine has focused only on addiction. But beneath that surface, mental health is quietly unraveling.

Across the United States, people are facing the aftershocks of cocaine use in their relationships, careers, and minds. Some are battling depression they never had before. Others can’t shake the anxiety that started after a “party phase.” A few are struggling with full-blown psychosis, and don’t know where to turn.

But here’s the truth: you are not alone—and this doesn’t have to be your story’s end.

Whether you’re a young professional in New York, a mother in Ohio, a veteran in Arizona, or a student in Florida—help exists. Therapy is no longer locked behind a clinic door. It’s on your screen. It’s in your community. It’s waiting to meet you where you are.

Recovery is not just about quitting cocaine. It’s about remembering who you are underneath the chaos. It’s about finding peace in your mind—not just sobriety in your routine.

And that begins when you stop asking “What’s wrong with me?”

And start asking “What happened to me?”

About the Author

Naincy Priya is a seasoned mental health writer and researcher with a deep focus on addiction psychology and trauma-informed recovery. With over a decade of experience crafting evidence-based content for therapy platforms, behavioral health clinics, and rehabilitation programs across the U.S., she brings empathy and expertise to every piece she creates. Naincy is especially passionate about uncovering the emotional and neurological layers behind substance use, making complex topics accessible to everyday readers. Through her writing, she aims to bridge the gap between clinical insight and real-world understanding—helping individuals feel seen, supported, and empowered to heal.

Transform Your Life with Expert Guidance from Click2Pro

At Click2Pro, we provide expert guidance to empower your long-term personal growth and resilience. Our certified psychologists and therapists address anxiety, depression, and relationship issues with personalized care. Trust Click2Pro for compassionate support and proven strategies to build a fulfilling and balanced life. Embrace better mental health and well-being with India's top psychologists. Start your journey to a healthier, happier you with Click2Pro's trusted online counselling and therapy services.