Body Dysmorphia in the Age of Filters: When Selfies Distort Reality

Table of Contents

- The Filtered Reality Crisis: Why Everyone Looks ‘Perfect’—and That’s the Problem

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) vs. Just Feeling Insecure: Where’s the Line?

- The Teenage Trap: Body Image Crisis Among U.S. High Schoolers

- The Profession Effect: Models, Nurses, Influencers, and Tech Workers at High Risk

- The Mental Health Fallout: Anxiety, Depression & Social Withdrawal

- Online Therapy for Body Dysmorphia: Why It's Becoming a Lifeline

- Mirror Checking, Reassurance Seeking & Surgery Obsession: Hidden Symptoms You May Miss

- How to Stop Body Checking and Heal Your Relationship with Your Image

- Should You Quit Social Media? The Real Impact of a Filter-Free Life

- Real Recovery Stories: From Filter Addiction to Self-Acceptance

- FAQs

- About the Author

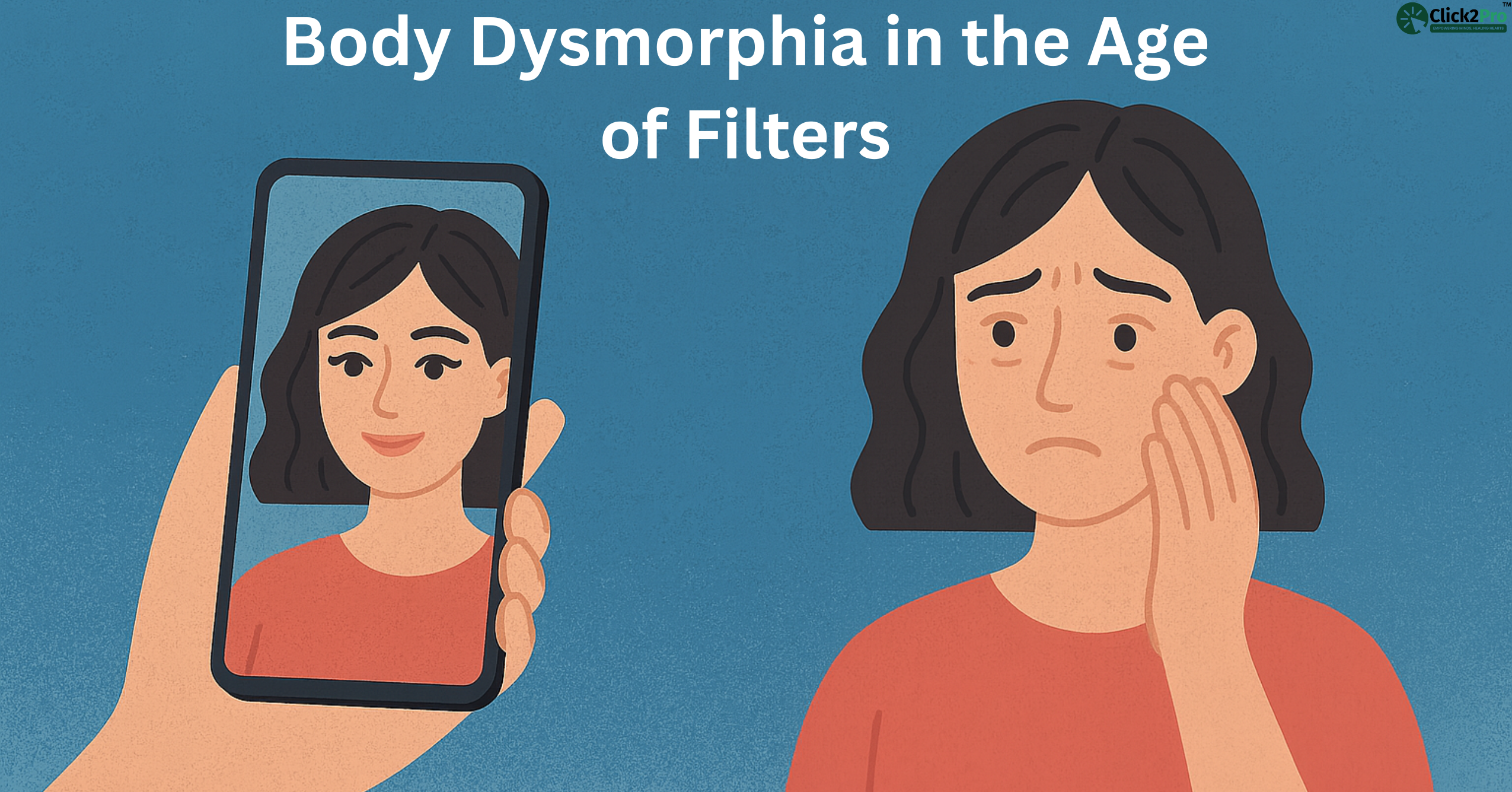

The Filtered Reality Crisis: Why Everyone Looks ‘Perfect’—and That’s the Problem

There’s a moment that hits you—mid-scroll on Instagram, TikTok, or Snapchat—when you realize everyone seems to have flawless skin, razor-sharp cheekbones, a perfectly symmetrical face, and eyes that sparkle unnaturally. It’s not just celebrities anymore. It’s your coworkers, classmates, and even your neighbor's teenage daughter. They all seem “perfect,” and somehow… you don’t. But what if none of it is real?

We are living in an age where augmented reality filters are no longer just fun add-ons. They are digital masks people wear so often that they forget what they actually look like. From California to Florida, filtered selfies are becoming the norm. Apps like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat have integrated face-altering filters that slim noses, smooth skin, widen eyes, and lift cheekbones—all within seconds.

This seemingly harmless technology is fueling a silent mental health crisis, especially among Gen Z and young Millennials in states like New York, Texas, and Illinois. The more filters we use, the more our brain starts to believe that these digital versions are the “ideal” us. And every time we look into a real mirror, there’s a cognitive dissonance—a jarring emotional disconnect between what we see online and who we are offline.

In therapy rooms across the U.S., mental health professionals are seeing a growing number of clients—especially teens and women—who report deep dissatisfaction with their real-life appearance. Some refuse to take unfiltered photos. Others won’t join Zoom calls unless their video is turned off or filtered. These aren’t superficial concerns. They are early signs of something much deeper: a distorted self-image that may spiral into clinical body dysmorphic disorder.

Filtered images are not just visual enhancements—they become personal benchmarks. Young adults often describe feelings of panic when their real face doesn’t match the way they appear in selfies. They spend hours tweaking their lighting, angle, and makeup just to mirror what an algorithm can do in milliseconds. In high schools and colleges from Los Angeles to Miami, students report skipping class, avoiding social events, and even refusing to leave the house because they feel “too ugly.”

We’re not just seeing a cultural shift—we’re witnessing a psychological transformation. What used to be a fun digital tool is now a primary mirror. And that mirror lies. But our minds still believe it.

When you hear terms like “Snapchat dysmorphia,” it’s not just a viral label. It’s a growing phenomenon backed by real mental health consequences. It starts with filters. It ends with surgery requests, social withdrawal, anxiety, and in many cases—depression.

As a psychologist, I’ve listened to stories from clients in both urban and rural areas—clients who no longer recognize themselves, and worse, no longer trust what they see in the mirror. Their distress is real. Their fear of being seen is real. And it’s not vanity. It’s psychological distress brought on by technology that sells beauty as perfection—and perfection as necessity.

This filtered reality isn’t just shaping how we see ourselves—it’s changing who we believe we are. That’s the danger. And that’s why body dysmorphia is on the rise in the age of filters.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) vs. Just Feeling Insecure: Where’s the Line?

Almost everyone has moments when they feel unattractive. Maybe your skin broke out before an event. Maybe your hair just won’t cooperate. That’s human. But body dysmorphic disorder—BDD—is not just about feeling insecure now and then. It’s a serious and diagnosable mental health condition that can consume someone’s entire life.

The line between insecurity and BDD isn’t always clear from the outside. Both may involve dissatisfaction with appearance. Both may trigger social anxiety. But here’s where things start to diverge: BDD involves persistent, obsessive preoccupation with one or more perceived flaws that are either minor or entirely imagined. And these obsessions aren’t occasional—they can dominate several hours of someone’s day.

Let’s take a real example. A 22-year-old college student in Ohio becomes convinced her jawline is too weak. She’s not teased, no one comments on it, and friends don’t even notice anything unusual. Yet, she begins avoiding dates, refuses to be photographed, and spends hours watching jawline exercises on YouTube. She skips class to research chin surgeries. This is not a passing insecurity—it’s BDD.

One hallmark of BDD is repetitive behaviors. People may check mirrors obsessively, compare themselves to others online, seek constant reassurance, or use heavy filters to “fix” their flaws. Paradoxically, others might do the opposite—avoiding mirrors entirely or refusing to have their picture taken at all.

In professions where image plays a central role—like modeling, nursing, media, or fitness—the lines can blur even more. A flight attendant in California, for instance, might develop a fixation on her under-eye bags. Despite getting 8 hours of sleep, drinking water, and using skincare, she spends thousands on under-eye fillers that offer no relief. Each procedure leaves her more dissatisfied. Her identity becomes fused with this one perceived flaw.

Another layer of complexity is muscle dysmorphia, which often affects men. This is when individuals believe they’re too small or not muscular enough, even when they are objectively fit or even bulky. Men in states like Texas and Florida, where gym culture is strong, are reporting increasing rates of compulsive weight training, steroid use, and body checking—all tied to distorted self-perception.

BDD also affects how people engage with others. Relationships suffer. Work performance drops. Depression and anxiety often co-exist. In fact, research from the National Institutes of Mental Health has shown that individuals with BDD are at a significantly higher risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This is not a condition about vanity. It’s a condition about distortion, obsession, and suffering.

One reason BDD can be difficult to detect is because sufferers often become experts at hiding it. They may appear confident on social media. They may post selfies regularly. But what’s hidden behind the scenes is the hours spent editing, the dozens of rejected photos, the panic attacks when a filter glitches or a photo gets posted unedited.

In therapy, what we often uncover is a deep-rooted belief: “I am unacceptable the way I am.” Not just unattractive—but unworthy. And because this belief is reinforced every day by comparing culture and filtered realities, healing takes time. But it is possible.

The first step is understanding that BDD is not “being too sensitive.” It’s not vanity. It’s a serious mental health issue that affects people from all walks of life—students, nurses, engineers, stay-at-home parents, and influencers alike.

So how do you know when it’s “just insecurity” and when it’s something more? Here are a few questions therapists often explore:

-

Is this concern taking up more than an hour of your day?

-

Are you avoiding things you used to enjoy because of how you look?

-

Do you feel distressed when you see your reflection or a photo of yourself?

-

Are you constantly editing or filtering your images to the point where your real face feels foreign?

-

Have you considered surgery for a flaw others don’t even notice?

If the answer is “yes” to many of these, it may be time to explore professional support.

Many individuals with BDD find relief through cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and compassion-focused practices. Online therapy India options—like those offered by platforms such as Click2Pro—can provide a confidential, stigma-free space to begin healing, especially for those in remote or underserved U.S. states.

The bottom line? Feeling self-conscious is normal. But when it begins to dominate your life and distort your identity, it’s not “just insecurity” anymore. It’s time to take your pain seriously.

The Teenage Trap: Body Image Crisis Among U.S. High Schoolers

Walk through any high school hallway in the U.S. and it won’t take long to notice a quiet but overwhelming trend. Teenagers—especially girls—are glued to their phones, scrolling through filtered faces, staged bodies, and algorithm-driven ideals. While this may seem like normal behavior, what's happening underneath is a deep and growing crisis in body image and self-worth.

According to the CDC’s 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, nearly 3 in 5 high school girls (57%) in the U.S. said they felt persistently sad or hopeless during the past year. That’s the highest level reported in a decade. And while sadness can come from many places, body image is one of the most powerful contributors, especially in this age of constant digital exposure.

What’s happening is more than just social comparison. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok aren't just showcasing beauty—they’re redefining it. For many American teens in states like Florida, Michigan, and Illinois, "normal" no longer means a real face in the mirror. It means a filtered face on screen.

The problem isn’t that they want to look good. It’s that they’re learning to hate their real selves.

Therapists across the U.S. are reporting younger and younger clients—some as young as 11—struggling with body dysmorphia symptoms. These kids aren’t just upset about acne or a bad hair day. They’re crying in therapy over “fat” knees or “huge” foreheads. They refuse to go to school because they can’t get their eyeliner symmetrical. They edit every photo before they post—even private ones—and panic if anyone shares an unfiltered image.

One teen from New Jersey told her counselor that she skipped an entire semester of in-person school because she didn’t want people to see her “real nose.” Another from Texas started refusing family dinners because she feared gaining weight would ruin her “aesthetic.”

What makes this worse is that many of these behaviors are normalized online. Trends like “What I Eat in a Day,” “Hot Girl Walks,” or “Facial Symmetry Tests” teach young people that their worth is tied to how photogenic they are. There’s constant pressure to improve, shrink, contour, or disappear behind the perfect filter.

Parents often miss the signs. They may think their child is just shy, uninterested, or dramatic. But avoidance behaviors—like never taking photos, skipping events, covering mirrors, or obsessively watching beauty routines—are red flags.

In states like California and New York, where influencer culture is mainstream, schools are beginning to recognize this issue as more than cosmetic. Some school counselors have started running digital body image workshops, but many students still suffer silently. The shame attached to “not being enough” keeps them quiet.

It’s not about vanity. It’s about identity. These teens aren’t trying to be famous—they’re trying to feel acceptable. But when the standard of beauty is generated by software, it's a battle they will never win without support.

The teenage brain is still developing. It’s naturally prone to black-and-white thinking, emotional sensitivity, and social comparison. Add daily exposure to unattainable beauty and you have a recipe for lasting harm—distorted self-image, anxiety, depression, and in some cases, eating disorders or self-harm.

The good news? Early intervention works. Schools that introduce body image literacy and media education show significant improvements in students’ self-esteem. More importantly, open conversations at home—without judgment—can make all the difference.

If you're a parent, teacher, or school counselor, take note: when a teenager becomes obsessed with appearance, it's not a phase. It could be a cry for help.

The Profession Effect: Models, Nurses, Influencers, and Tech Workers at High Risk

Body dysmorphia doesn't just impact teens. In fact, it thrives quietly among working professionals in the U.S.—especially in careers where appearance is judged, displayed, or scrutinized. While influencers and models may seem like obvious candidates, the truth is that body image distress also hits nurses, fitness instructors, hospitality workers, and even remote tech employees.

Let’s start with the obvious: influencers and models. In states like California and Florida, where content creation is a booming industry, maintaining a certain "look" isn't optional—it’s a job requirement. The pressure to look camera-ready at all times leads many to overuse filters, pursue unnecessary cosmetic enhancements, or develop obsessive appearance-focused routines.

One model from Los Angeles shared during a support group that she had undergone three surgeries in one year just to look like her filtered selfies. Even after the procedures, she felt more disconnected from her appearance than ever before. She eventually quit modeling and started therapy.

But you don’t have to be famous to suffer. In the nursing profession—especially in states like New York, Pennsylvania, and Georgia—appearance expectations often go unspoken but are deeply felt. Nurses report feeling pressure to “look put together” despite working long, exhausting shifts. For many, the constant exposure to patients, families, and hospital staff triggers comparison and body scrutiny.

Then there’s the fitness industry. Personal trainers and gym instructors in places like Texas or Arizona often become hyper-aware of their physiques. While the focus may appear to be on health, for many professionals, there’s a shift from strength to appearance. The line between fitness goals and physical obsession can blur quickly. Many report body checking multiple times a day or refusing to post workout content unless they’ve edited or filtered their appearance.

Perhaps more surprising is the tech and remote work culture. In Silicon Valley and major hubs like Seattle or Chicago, professionals working over Zoom often rely on built-in filters, touch-up tools, and lighting tricks. While this may seem harmless, over time it can create a distorted mental image—especially if someone never sees their raw, unedited face during meetings.

Some workers develop anxiety about in-person events, fearing they don’t look “like themselves.” One software engineer admitted to skipping a team retreat because she couldn’t “control the lighting” in real life.

It’s a subtle but powerful shift: when our real face starts to feel like a letdown compared to our virtual one, we may be in dangerous psychological territory.

Cosmetic surgeons across the U.S. report that patients are no longer bringing in celebrity photos—they’re bringing in their own filtered selfies. In fact, a 2024 survey by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery revealed that over 55% of surgeons noted this trend. This isn’t just about wanting to enhance appearance—it’s about erasing real-life features to match digital illusions.

And the cost isn’t just financial. Repeated cosmetic procedures often fail to resolve the core emotional distress of BDD. The dissatisfaction persists, and the cycle continues.

In therapy, many professionals express feeling isolated. “I know it sounds shallow,” they’ll say. But it’s not about shallowness. It’s about a mismatch between identity and self-image—a dissonance that disrupts work, relationships, and self-worth.

Professionals often delay getting help because they fear judgment. But mental health doesn’t discriminate by career. The person with the best LinkedIn profile or most polished Instagram feed may be silently suffering from a distorted view of themselves.

If you or someone you know is in a career that values appearances, it’s worth asking: Am I working for my goals, or am I working to be accepted based on how I look? That one question can open the door to healing.

The Mental Health Fallout: Anxiety, Depression & Social Withdrawal

When someone is struggling with body dysmorphia, it rarely stops at appearance-related thoughts. What begins as a private insecurity can quickly evolve into a deeper emotional storm—one that touches every area of life. In therapy rooms from Boston to Boise, people are opening up about how their self-image struggles are linked not just to dissatisfaction but to full-blown mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and even suicidal ideation.

One of the most heartbreaking realities of body dysmorphia is that it doesn't stay skin-deep. It takes over routines, ruins relationships, and hijacks the nervous system. Research from the National Institutes of Mental Health shows that people with BDD are at four times higher risk of developing major depressive disorder. For many, the shame of not meeting internal standards creates a painful emotional loop that feels impossible to break.

Here’s how it unfolds for many Americans: You wake up, look in the mirror, and immediately feel panic. Your skin doesn’t look smooth enough, your face feels asymmetrical, or you think your nose has “changed overnight.” That one thought sets off a chain reaction—canceling plans, missing work, skipping class, or avoiding social media completely. You become anxious in everyday situations, terrified someone might see the flaw you’re trying so hard to hide.

Social anxiety soon follows. A young woman in Illinois shared how she started avoiding video calls at her corporate job because she couldn’t stop looking at her own face on-screen. She eventually stopped attending meetings altogether, fearing judgment—even though no one had ever commented on her appearance.

In New Mexico, a high school senior with undiagnosed BDD told his therapist that he stopped hanging out with friends, avoided dating, and wore hoodies every day—even in summer—to hide perceived flaws in his body. What started as a self-esteem issue evolved into chronic isolation.

Social withdrawal is one of the clearest signs that body dysmorphia is affecting mental health. Many sufferers report feeling safer when alone, not because they want solitude, but because being seen feels threatening. Over time, this loneliness reinforces the belief that their real appearance is “unacceptable.”

Anxiety and panic attacks are also common. When faced with an unexpected photo, a group selfie, or even a surprise FaceTime call, people with BDD often feel intense fear or disgust. Their heart races, their breathing quickens, and they may freeze, cry, or dissociate. These reactions aren’t vanity—they are trauma responses rooted in deep distress.

In some cases, body dysmorphia also overlaps with eating disorders, particularly in states where appearance culture is strong—like California, Texas, and New York. People may begin strict dieting, over-exercising, or engaging in purging behaviors to “fix” imagined flaws.

But here’s what often goes unseen: many individuals with body dysmorphia suffer in silence. They may appear high-functioning. They go to work, show up on social media, laugh in group chats—but inside, they are at war with themselves. And because this internal battle isn’t visible, it’s easy to miss.

As a psychologist, I’ve seen how untreated BDD erodes confidence, steals joy, and plants seeds of despair. It’s not something that gets better on its own. It requires compassion, support, and most importantly, proper treatment.

That’s where therapy comes in—not to make someone love their reflection overnight, but to help them untangle their identity from their appearance and find relief from the obsessive thinking that’s keeping them trapped.

Online Therapy for Body Dysmorphia: Why It's Becoming a Lifeline

One of the most promising developments in mental health care in recent years has been the rise of online therapy, particularly for body image-related disorders like BDD. For many Americans who feel too ashamed, too busy, or too anxious to walk into a therapist’s office, online therapy is not just convenient—it’s life-changing.

In a 2024 study by the American Psychological Association, 43% of Gen Z respondents reported they would choose online therapy over in-person treatment. And it’s easy to see why: it offers privacy, flexibility, and accessibility—especially for those in underserved states like Idaho, Arkansas, or South Dakota, where mental health providers are scarce.

Clients dealing with body dysmorphia often feel deeply self-conscious. Some can’t bear the idea of sitting in front of someone face-to-face, especially without a filter. Others worry about being judged for their concerns, fearing they’ll be told they’re just “overreacting” or “being vain.” With online therapy, many of those barriers disappear.

Platforms like Click2Pro provide a safe space for individuals to speak openly about their fears, routines, and struggles—without needing to leave their home. Therapists can meet them where they are, both emotionally and geographically.

So, how does online therapy actually help with BDD?

First, most licensed therapists treating BDD rely on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)—an evidence-based approach that helps individuals recognize and challenge distorted thinking patterns. For example, someone might believe, “My nose is disgusting, and everyone is staring at it.” CBT would work to replace that belief with something more balanced and accurate, like, “My nose isn’t perfect, but that doesn’t define my worth or how others see me.”

Second, Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) is often used to reduce compulsive behaviors like mirror checking, reassurance seeking, or endless photo retouching. A therapist might encourage a client to post an unfiltered selfie—or go outside without makeup—and then sit with the discomfort until it gradually fades. Over time, the brain learns that nothing catastrophic happens when they’re “seen.”

Third, online therapy also allows for integrated care. Clients with BDD often deal with co-occurring conditions like depression, OCD, or anxiety. Working with a therapist who understands the full picture ensures that treatment is holistic and not symptom-specific.

Another benefit of online therapy is greater consistency. Clients don’t have to cancel due to traffic, long commutes, or self-consciousness. They can attend sessions in a safe environment—sometimes even with the camera off in early stages.

And perhaps most importantly, online therapy breaks the shame cycle. It tells clients: You are not alone. What you’re feeling is valid. And help is here, on your terms.

That flexibility matters deeply for people in professions like modeling, tech, or healthcare—where taking an hour off for therapy isn’t always feasible. It also benefits teens who may not feel comfortable talking to their school counselor, but will open up from the privacy of their bedroom.

At Click2Pro, we’ve seen clients make incredible progress—reclaiming their self-worth, reducing obsessive rituals, and finally feeling comfortable in their own skin. Online therapy may not replace the mirror, but it can transform how people see themselves in it.

Mirror Checking, Reassurance Seeking & Surgery Obsession: Hidden Symptoms You May Miss

Body dysmorphia rarely announces itself loudly. It often hides behind habits that seem harmless—at least at first. But these everyday behaviors, when driven by obsessive thoughts and emotional distress, are not just quirks. They’re warning signs.

Take mirror checking. It’s one of the most common but overlooked symptoms of body dysmorphia. Someone may check their reflection in every surface they pass—mirrors, car windows, store doors, phone cameras. But it’s not about admiration. It’s about surveillance. They’re scanning for flaws, over and over, hoping that maybe this time the flaw will be gone. Or they’re bracing for how “bad” they think they’ll look.

In therapy sessions from Chicago to Charlotte, clients often admit they lose hours each week in front of mirrors. They zoom in on photos, flip the camera to “check” their nose or chin, or analyze their face for unevenness. Many don’t even realize how often they do it—until they try to stop.

Reassurance seeking is another red flag. A person might repeatedly ask friends, “Does my skin look okay today?” or “Are you sure my face isn’t weird in that picture?” On the outside, it may seem like they're fishing for compliments. But underneath, it’s anxiety-driven behavior. The need for external validation becomes compulsive—yet the comfort never lasts.

Then there’s the obsession with cosmetic procedures. This is where body dysmorphia can take a dangerous turn. What begins as a desire to “enhance” quickly turns into a desperate attempt to erase. People with BDD often seek consultations with dermatologists, aestheticians, and plastic surgeons—not because they’re chasing glamour, but because they genuinely believe something is wrong with their face or body.

In states like California and Florida, where cosmetic surgery is more accessible and normalized, mental health professionals report an alarming rise in clients who have undergone multiple, unnecessary procedures—often to "correct" imagined flaws. Yet post-surgery, the relief is short-lived. Many soon find a new flaw to fix.

A 29-year-old nurse in Georgia shared her story of having four different procedures on her lips. Not one of them brought peace. Instead, her anxiety worsened, especially when the filters she used daily began to no longer match her real face.

Avoidance behaviors are also common but easily missed. Some people with BDD avoid mirrors entirely. They might cover bathroom mirrors with towels, dim the lights in their home, or use their phones with the selfie camera taped over. Others avoid photography altogether, insisting they’re “not photogenic” or “don’t like how they look.” The truth? They’re in pain.

In some cases, this leads to extreme self-isolation. Individuals refuse to attend weddings, job interviews, or reunions—not because they’re shy, but because they don’t want to be seen.

Professionals in high-visibility fields like hospitality, aviation, or online content creation are especially vulnerable. When appearance becomes a part of their job, these hidden symptoms of body dysmorphia can explode under the pressure.

If you or someone you know displays these behaviors often—and they interfere with daily life—it may be time to ask: Is this just self-consciousness, or is something deeper going on?

These habits aren’t about vanity. They’re about pain. And recognizing the symptoms is the first step toward healing.

How to Stop Body Checking and Heal Your Relationship with Your Image

If you’ve ever caught yourself zooming into your face on a selfie, avoiding mirrors, or using five filters before posting a picture, you’re not alone. But if these habits have started to control your emotions, dictate your schedule, or affect your self-worth, it might be time to take back control—and no, that doesn’t mean changing how you look. It means changing how you see yourself.

Stopping body checking isn’t easy. It can feel like breaking an addiction. But it’s one of the most effective ways to reduce the grip body dysmorphia has on your mind.

One of the first things therapists recommend is mirror fasting. This doesn’t mean covering every mirror in your house. It means limiting how often—and how long—you look. Set a timer for 30 seconds in the morning, just to check your hygiene or grooming. Then walk away. The goal is not to avoid your reflection entirely, but to stop obsessively monitoring it.

Next comes reframing self-talk. Most people with body dysmorphia have an internal script filled with harsh, judgmental thoughts like “I look disgusting,” or “No one will like me looking like this.” In cognitive behavioral therapy, we work to challenge these beliefs. For example, instead of saying, “I look awful in this picture,” a reframe might be: “This picture doesn’t define me. I’m more than how I appear in one photo.”

Another powerful step is to post an unfiltered image—even if you feel scared. Why? Because exposure therapy helps retrain the brain. When you take small, calculated risks (like posting a photo without smoothing your skin), your anxiety may spike temporarily. But over time, your brain learns that the feared consequences—rejection, humiliation, disgust—don’t actually happen. And with repetition, your confidence grows.

Gratitude journaling can also shift your focus. Instead of tracking flaws, write down three things your body does for you each day. Maybe it allows you to hug your child, carry groceries, or run a mile. This builds body functionality awareness—a key piece in restoring image neutrality.

Therapists often introduce the concept of body neutrality—the idea that your body doesn’t have to be beautiful or perfect to be respected. It just has to be yours. It deserves care and comfort, even on days you don’t love how it looks.

Some clients also benefit from limiting time on image-based platforms. Taking breaks from Instagram, Snapchat, or TikTok—even for a weekend—can give your brain room to breathe. You might realize that your body image improves when you're not constantly comparing yourself to others.

Apps like Reflectly, Woebot, or Rise Up + Recover help track intrusive thoughts and provide CBT-based journaling prompts. They don’t replace therapy, but they do support the journey.

Support groups, both online and offline, offer another layer of healing. Sometimes, just hearing someone else say, “I feel that way too,” can break the isolation and shame that keeps BDD in power.

Most importantly, forgive yourself. You didn’t choose to feel this way. These thoughts are not your fault. They are the result of a culture, a digital system, and often—unresolved pain. But you can choose recovery.

Healing your relationship with your image takes time. Some days, it’ll feel easier. Other days, it’ll feel impossible. But every step—no matter how small—is a rebellion against a world that profits from your insecurity.

You deserve peace. And it doesn’t come from changing your face. It comes from changing your focus.

Should You Quit Social Media? The Real Impact of a Filter-Free Life

It's a question more people are quietly asking themselves these days: Should I just quit social media altogether? For those struggling with body dysmorphia or image anxiety, the platforms that once felt fun now feel like pressure cookers. And the truth is—stepping away can be powerful. But it’s not the only answer.

Social media isn't inherently harmful. For many, it’s a tool for connection, creativity, and even activism. But the problem begins when scrolling becomes comparison, and filters become identity.

In states like Utah and Arkansas, parents and lawmakers are already pushing back. The Teen Filter Disclosure Act, proposed in early 2025, requires social media companies to label filtered or AI-enhanced photos—especially in influencer posts targeting minors. Similar discussions are underway in states like California and Massachusetts. The cultural tide is shifting. People are starting to ask: What is this doing to our mental health?

Some users have gone cold turkey. A 26-year-old artist in Oregon described deleting Instagram for 30 days and noticing a huge drop in anxiety. She reported better sleep, clearer thinking, and, most notably, a healthier relationship with her appearance. Without the constant exposure to “perfect” faces, her own felt enough again.

But quitting social media isn’t realistic—or necessary—for everyone.

Instead, some people are choosing a filter-free feed. They unfollow beauty accounts, mute triggering hashtags, and follow creators who post unedited, body-positive content. These simple changes can reset your brain’s baseline. When you're no longer flooded with “perfect,” real starts to look beautiful again.

Another strategy is time-blocking. Set specific times to check social media—maybe 30 minutes in the evening. Turn off notifications. Reclaim control. The goal isn’t to disappear from the digital world. It’s to protect your mental health from constant digital distortion.

And finally, be intentional. Ask yourself before posting: “Am I sharing this because I want to, or because I feel I have to?” If it’s the latter, take a step back.

Social media should be a tool, not a trap. You can use it without being used by it. And sometimes, freedom starts with just one unfiltered photo.

Real Recovery Stories: From Filter Addiction to Self-Acceptance

Behind every mental health condition is a human story. And when it comes to body dysmorphia, real people are learning that healing doesn’t require a new face—it requires a new perspective. At Click2Pro, we’ve supported hundreds of individuals through this journey. Here are just a few of the stories that inspire us—and may inspire you.

Amanda from Chicago, IL, once spent nearly two hours a day editing selfies. She used filters that changed her eye color, reshaped her face, and blurred every blemish. She refused to meet new people in person, terrified they’d think she was a “catfish.” After joining an online therapy program and starting weekly sessions, she began to challenge her thoughts. Six months later, she shared an unfiltered photo for the first time and wrote: “I was scared. But now, I feel proud. I showed up as myself.”

Devin, a fitness trainer from Phoenix, AZ, used to check the mirror 20+ times a day, convinced he wasn’t muscular enough. Despite being in excellent shape, he wore baggy clothes and avoided gym selfies unless heavily filtered. Therapy helped him recognize his distorted self-image and build self-worth around his abilities—not just his looks. Today, Devin teaches young athletes how to set goals rooted in strength, not shame.

Leila, a college student from New York, had undergone two cosmetic procedures by age 21. When her anxiety didn't go away—and instead got worse—she reached out to an online support group. From there, she started therapy at Click2Pro. She learned how her fear of not being “camera ready” stemmed from early bullying and perfectionist patterns. Now, she’s learning to speak kindly to herself and has become a mental health advocate on campus.

What do these stories have in common? None of them required a physical transformation. They all started with the same shift: recognizing that their pain was valid, and they didn’t have to live with it alone.

Recovery from body dysmorphia isn’t linear. There are setbacks. But there’s also hope—real, tangible hope. Through therapy, education, and community, people are reclaiming their lives. And so can you.

Whether you’re a teen trying to survive high school in Florida, a nurse in Ohio under pressure to look “polished,” or a content creator in LA feeling burned out by filters—you’re not alone.

Healing is possible. And it starts with being seen, not perfected.

FAQs

-

Is body dysmorphia caused by filters?

Filters don’t directly cause body dysmorphia, but they can trigger or intensify it—especially in people already prone to perfectionism or anxiety. Repeated exposure to edited images sets unrealistic beauty standards. Over time, individuals may feel disconnected from their unfiltered face, leading to distorted self-perception.

-

What is Snapchat dysmorphia?

Snapchat dysmorphia refers to a condition where people become fixated on looking like their filtered selfies. It often leads to a desire for cosmetic surgery to replicate digital features—like smoother skin, smaller noses, or larger eyes. Surgeons across the U.S. have reported a rise in clients bringing filtered photos of themselves as surgery goals.

-

How do I know if I have body dysmorphia or just low self-esteem?

While both involve self-image concerns, body dysmorphia is more intense and persistent. If you spend over an hour a day fixated on one or more perceived flaws, avoid social situations due to appearance, or constantly edit photos to feel “okay,” you may be experiencing symptoms of BDD. A licensed therapist can provide a formal evaluation.

-

Can online therapy really help with body dysmorphia?

Yes. Online therapy, particularly CBT-based, is a proven and effective treatment for body dysmorphia. It helps challenge distorted beliefs, reduce compulsive behaviors, and rebuild self-image. For those in remote or high-pressure environments, online options offer privacy, flexibility, and ongoing support.

-

Why do I feel ugly in unfiltered photos but okay with filters?

Filters create an artificially enhanced version of your face. When you see yourself unfiltered, your brain compares it to the edited image, often making your real face seem unfamiliar or “less than.” This gap between digital and real can trigger negative self-judgment. It’s not about how you look—it’s about how your brain interprets the difference.

-

What are the first steps to stop body checking?

Start by limiting mirror time and avoiding zoomed-in selfie reviews. Replace body-checking routines with grounding habits like journaling or movement. Set specific “check-free” windows during the day. Online therapy can guide you through exposure-based techniques that gently reduce the compulsion.

-

Can men have body dysmorphia too?

Absolutely. While often overlooked, men experience BDD—particularly in the form of muscle dysmorphia. They may feel “too small” even when muscular, leading to excessive gym time, strict diets, or steroid use. Many men suffer in silence due to stigma, but support is available and effective.

About the Author

Charmi Shah is a seasoned psychologist and mental health writer with a decade of experience supporting individuals struggling with body image, anxiety, and identity-related challenges. Her work bridges the gap between clinical insight and everyday struggles, helping readers make sense of what they’re feeling and why it matters. With a Master’s degree in Clinical Psychology and a background in trauma-informed therapy, Charmi has worked with clients across diverse communities in the United States, including teens, young professionals, healthcare workers, and those in the entertainment and tech industries.

What makes Charmi’s writing stand out is her ability to communicate complex mental health concepts in a way that feels personal, relatable, and deeply human. She doesn't just write about disorders—she tells the stories behind them, giving voice to those who often suffer in silence. Her goal is always the same: to remind people that their pain is valid, their experience is real, and healing is possible.

Now a contributor at Click2Pro, Charmi combines evidence-based psychology with a compassionate, culturally-aware lens. She brings both expertise and empathy to every piece she writes, ensuring that each article does more than inform—it connects. Her writing is grounded in the belief that mental health conversations belong in everyday life, not just therapy rooms, and that education can be a powerful form of healing. Through her work, Charmi continues to challenge stigma, empower readers, and advocate for a world where everyone feels seen without needing to filter who they are.

Transform Your Life with Expert Guidance from Click2Pro

At Click2Pro, we provide expert guidance to empower your long-term personal growth and resilience. Our certified psychologists and therapists address anxiety, depression, and relationship issues with personalized care. Trust Click2Pro for compassionate support and proven strategies to build a fulfilling and balanced life. Embrace better mental health and well-being with India's top psychologists. Start your journey to a healthier, happier you with Click2Pro's trusted online counselling and therapy services.